Global goods prices have risen significantly across countries; this is partially transitory, caused by Covid and the Russia-Ukraine war, but also in part by the continuation of structural change, accelerated by these catalytic events. Here we discuss the difference between the inflationary environment in China and the West, to identify the underlying reasons for the differing headline numbers, and the structural movement that is often neglected but crucial in long-term investment.

Covid

Covid disruptively altered the long-term low inflation trend in the US. Supply disruption, trillions of dollars in stimulus and relief, and weak spending on services pushed goods prices high. However, with China’s response policy and economic structure very different, the effects of Covid have also not been the same as those seen in the US.

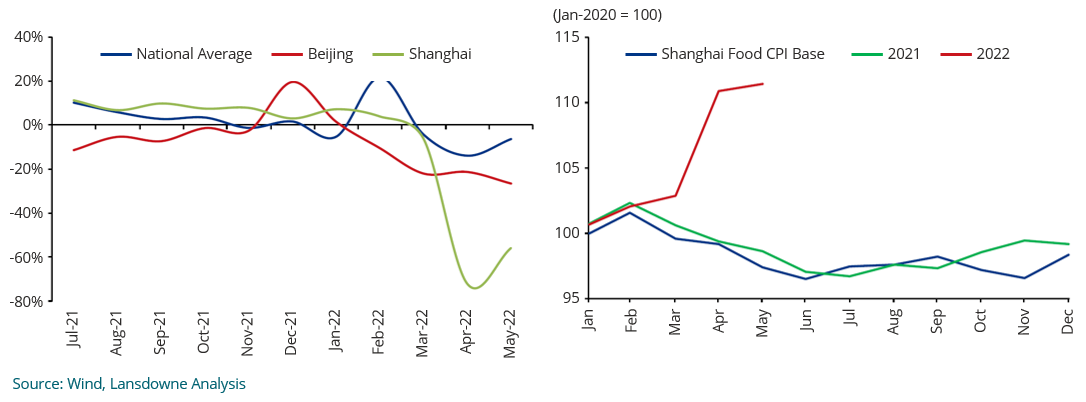

Firstly, unlike the US’s high dependency on import goods, China is largely self-sufficient. One has the largest trade deficit and one has the largest surplus. Global trade activities and logistics have been greatly affected by Covid, causing rising costs and delays. China’s Covid lockdown is local. Logistics outside affected areas have been largely normal. Fresh vegetables and eggs were in shortage as logistics in Shanghai were impeded by the lockdown and strict testing rules, resulting in a local inflation spike. Shanghai’s tracking volume dropped 80% and 60% in April and May respectively, and CPI rose to 4.6% (vs. the national average of only 2.1%). Once the lockdown ended, transportation of goods to Shanghai gradually resumed and the price dropped from its peak. In June, Shanghai CPI dropped to 2.9%.

Shanghai Road Freight Volume (YoY) and Food Inflation

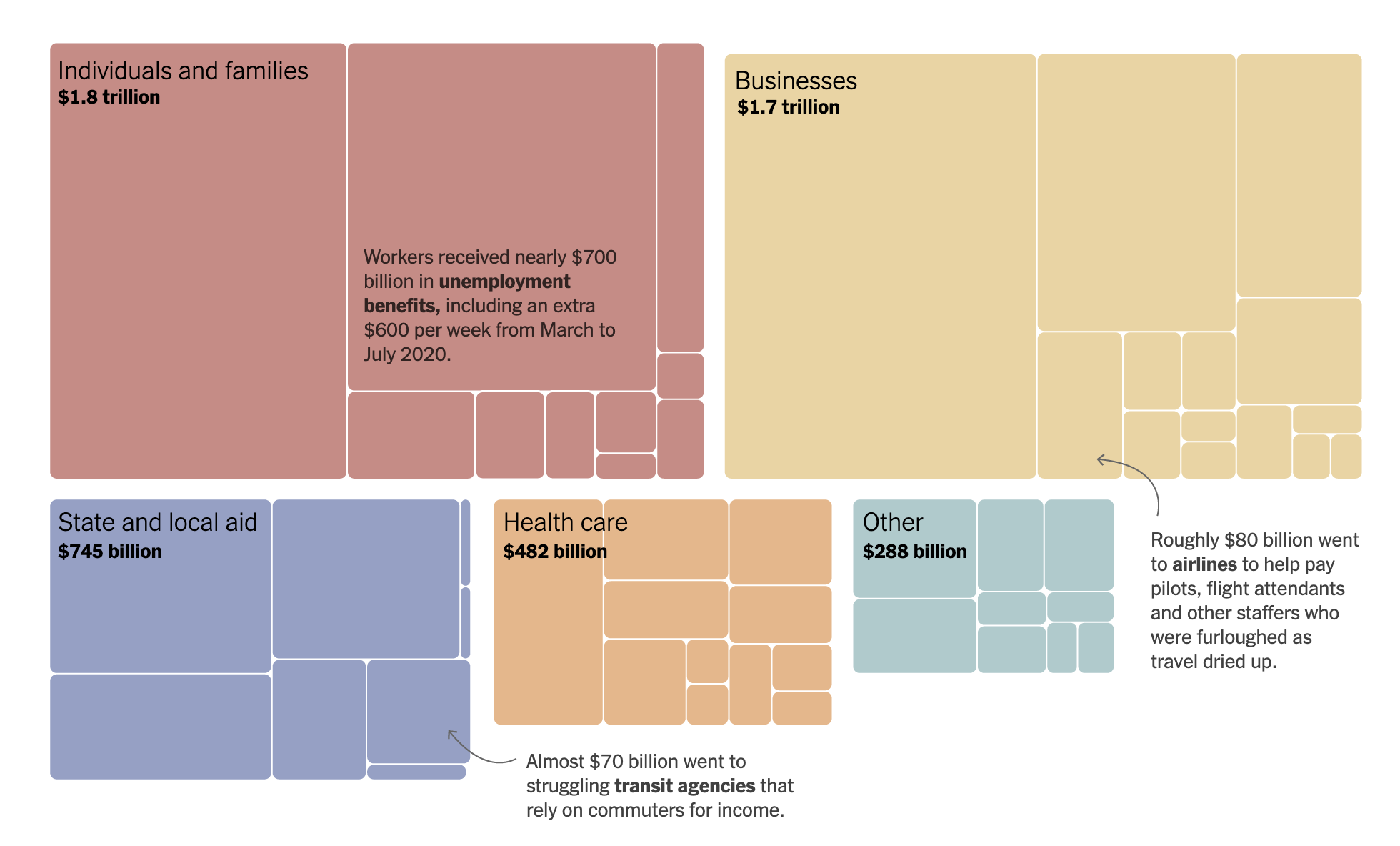

Secondly, China did not send helicopter money to consumers. In the US, $5 trillion in subsidies were given to residents and businesses. Many households’ income was higher than usual. Covid restrictions meant people had to curb spending on services and buy more goods, resulting in a demand-side boost. In comparison, Chinese consumers’ income was lower due to a generally weaker economy. Higher unemployment, slower investment and falling asset prices resulted in weaker consumer confidence, less spending, and higher savings. Covid’s effect in China is more deflationary.

US’s $5 trillion stimulus and relief funds

Source: New York Times

The War

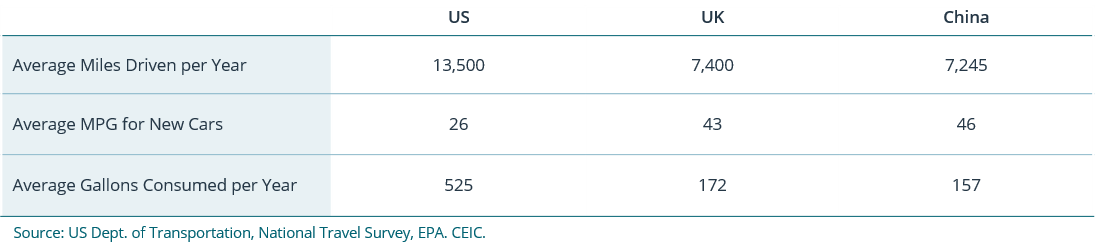

The Russia-Ukraine war is another black swan event pushing living costs up in the US. Energy accounts for 7.6% weight of the US CPI Index. Fuel and gas are significant components of daily spending and they are up by 42% in the year. The war also put upward pressure on food prices as US agricultural output dropped significantly in Russia and Ukraine, which accounts for a quarter of global wheat exports and a fifth of corn and grains. In the short term, the US will have difficulties boosting production to offset the shortfall. Food prices in the US are expected to increase by 10% in 2022.

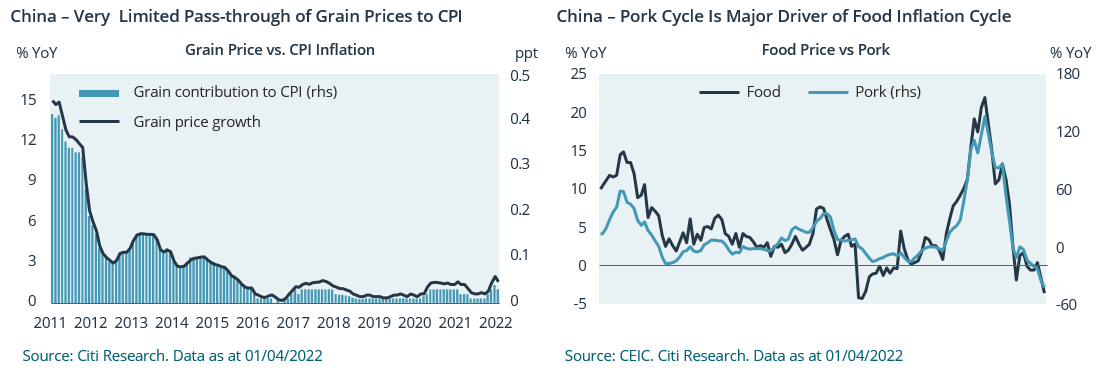

For China, as we have communicated in previous investment letters, the impact from the war is somewhat limited. Coal remains China’s primary energy source. Fuel is a small portion of Chinese consumer spend, and retail gas price is controlled by the state to smooth out volatility, with refiners absorbing losses from time to time. Inflation sensitivity to oil is low; a – 10% oil price causes 0.2% CPI change. Since June, China has adjusted the gasoline price downwards four times in a row.

The only food item where China relies heavily on imports is soybean, which is primarily sourced from the US and Brazil. For grain and rice, China currently has a very high inventory level.

In the short to medium term, the demand side of the Chinese economy is likely to stay weak due to uncertainty around exiting Covid, lukewarm stimulus and the structural slowdown of the housing market. Two moving parts driving inflation at the time of writing are the pork supply cycle – a very idiosyncratic factor – and how companies pass Production Price increases to consumers. They have contributed significantly to the variance of the headline number, but we think both are cyclical rather than structural.

Structural Changes

However, regarding the long-term, the structural economic rebalancing process continues to take place. Covid and the war served as catalysts that accelerated these changes. In these areas, despite the significant relative change, the prices tend to remain very low. The absolute effect is small compared to the total overall change and as such, they are usually overlooked and do not receive the same attention as pork and coal prices, for example. Items such as beverages, restaurants, labour and digital content belong to these imbalanced areas, where our long-term investments are also focused.

Since last year, food and beverage companies have started to raise their prices. This year, the trend continues, especially in areas where the product’s average selling price (ASP) is low. The instant noodle market leader Tingyi announced 10% price increase earlier this year, then the oligopoly competitor Uni-President followed suit. Even after the adjustment, the ASP is still at just 4 RMB/bag. Best-selling condiment company Lao Gan Ma, with 20% market share, raised its flagship hot sauce product price by 10% in March, to a mere $1.2 per bottle. Premiumization is taking place in the beer market. CR Beer said in the first half of the year the premium category grew at a double-digit rate, higher than the average pace; Heineken (their most premium brand) grew even faster. Companies’ topline growth has not been negatively affected by the price adjustment. Despite the percentage change being big, the absolute number is too small to impact consumer behaviour. In addition, these staples products are necessities with steady demand.

Buying meals from restaurants and having them delivered is also disproportionately cheap in China. Previously, the order platforms subsidised the consumers, the delivery riders earned very little and the dishes’ prices were low in the first place. In recent months, these three factors are changing to push the price of ordering deliveries as much as 30% higher, and even more in cities in lockdown. Firstly, because of the same reason mentioned above, online-to-offline platforms are raising monetisation rates to improve profitability. Many small businesses are complaining about Meituan for raising the commission rate. Secondly, many major cities are experiencing a shortage of riders. Lockdown in major cities made staying put less economical. Thirdly, in restaurants the cost of vegetables is rising due to seasonality and an increase in logistic costs. In June, many couriers reported ASP up 20%. We think labour, platform profitability and logistic costs are all trending up in the long term, and Covid simply accelerated this change.

After a harsh regulatory reset and a weak economic environment, tech companies have been cutting costs and shifting focus to profitability. We have been tracking this trend since Q1. Recently, more long-form video streaming platforms have announced price hikes. Last week, following iQiyi and Bilibili, Mengo TV announced an increase to the subscription fee of 15% to 22 RMB ($3.3) per month from August, a pace higher than the previous price adjustment. Unlike iQiyi and Bilibili, Mengo has already been profitable for a while.

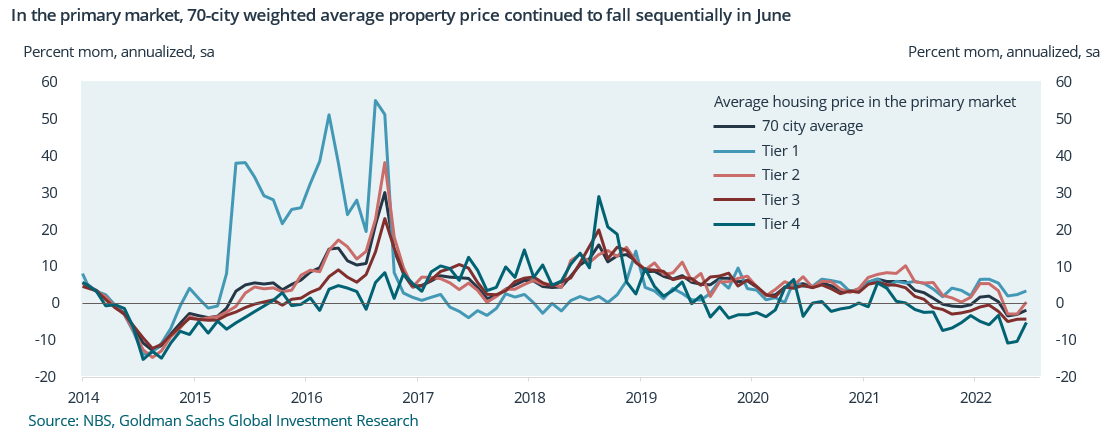

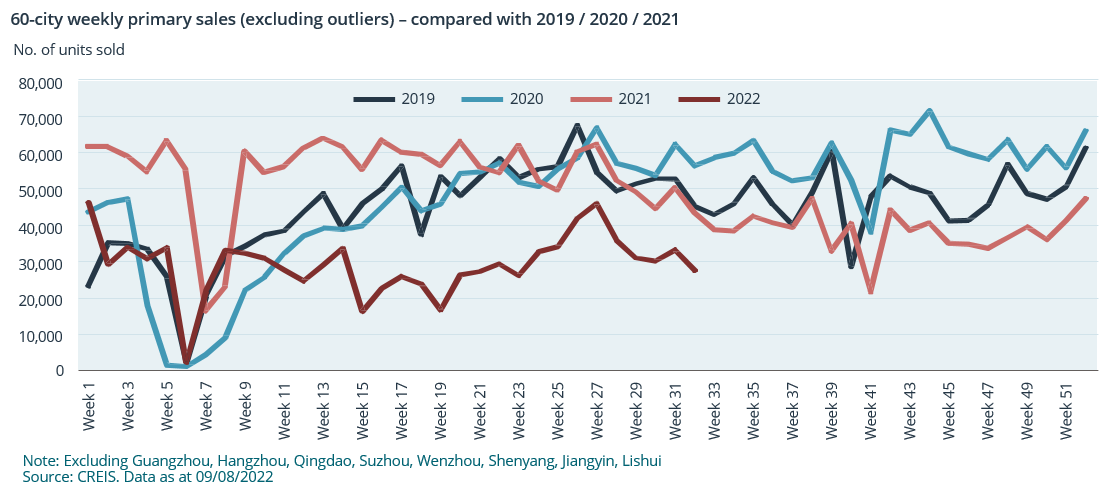

Meanwhile, some large ticket items are seeing prices deflate, dragging down overall headline numbers. Their prices are high compared to developed markets. The most obvious example is housing. Despite relaxing housing purchase restrictions and mortgage policies across the country, except for a few megacities like Shenzhen and Shanghai, most cities’ housing prices were trending down in June and deteriorated in July. Transaction volume also declined, indicating the government’s measures are ineffective, and more importantly, the housing market’s slowdown is structural.

China Property Price and Transaction Volume

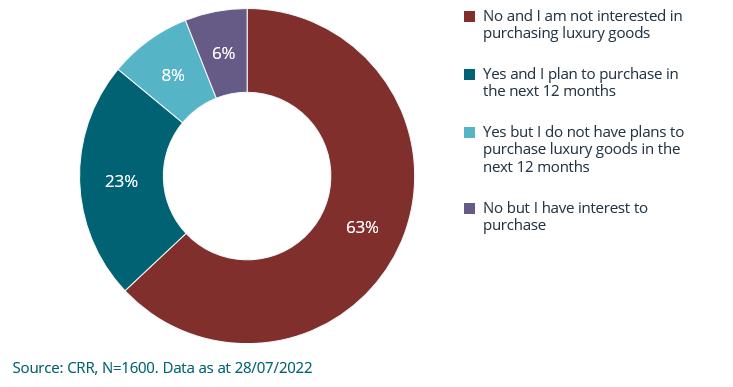

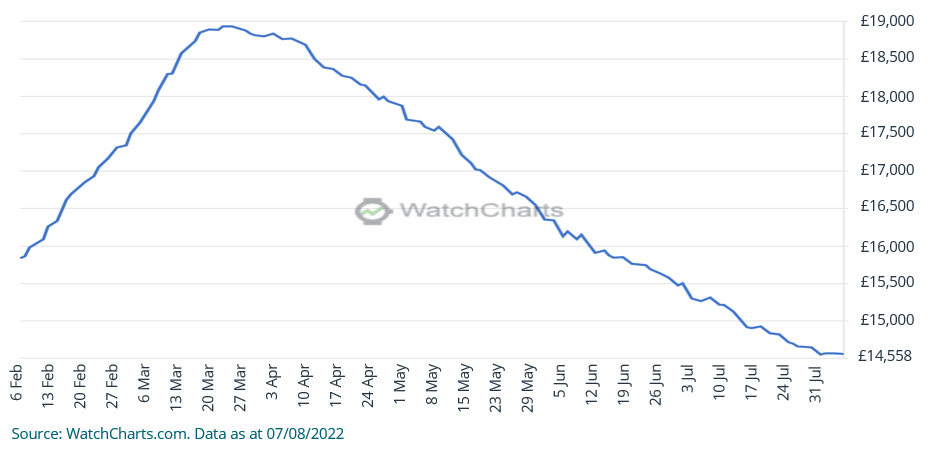

Luxury goods sales in China were greatly impacted by Covid and lockdown. The whole market was down 40% in the last three months, according to Barclays. Burberry just reported China sales down 35% YoY, in the previous quarter; Richemont said China was down 37%. According to a survey conducted by CLSA, over 63% of 1600 people asked do not plan to purchase luxury goods in the next 12 months. This number was 54% in November 2021. Watches have a higher ASP among the categories. The index tracking the price of the global high-end luxury watch market published by WatchChart shows the average price has dropped 25% since its peak in late March. In China, second-hand distributors report that since March, the price of best-selling Rolex and Patek Philippe models has dropped 40 – 50%.

Have you purchased luxury goods in the past 12 months?

WatchChart Luxury Watch Market Index

The data points collected here are worth noting because they are evidence of some structural trends in pricing in the economy we have identified and been tracking. A simple reading such as CPI would not capture these nuances – small in absolute terms but significant relatively. Covid and the war have accelerated the changes in many cases, but unevenly. We expect this structural rebalancing to continue to take place.

Disclaimer: The views expressed herein are the views of the Greater China team and not necessarily of Lansdowne Partners (UK) LLP as a whole. The content of this Article has been prepared by the Greater China team alone and is not, and has not been endorsed or approved by any other person. The article and the information, statements, opinions, interpretations and beliefs contained in it are those of the Greater China team and are provided in good faith, but no representation or warranty, either expressed or implied, is provided in relation to the accuracy, completeness or reliability of the contents of the Article, and no person shall be entitled to place any reliance on the Article or its contents. This Article is not intended to be, nor should it be construed as, investment, financial, tax or legal advice, or a recommendation to buy, sell or hold any security or other investment or pursue any investment strategy. Neither this letter nor any of its contents constitutes an inducement, offer or solicitation to purchase or sell any securities.

More Insights

Daniel Avigad explores what Europe can learn from Argentina’s radical reinvention under President Milei.

23 October 2025

Peter Davies spoke with Christian Mayes at Portfolio Adviser, who was interested to hear his views on why we believe UK banks represent a compelling contrarian opportunity

10 September 2025

Daniel Avigad discusses how political fragmentation and shifting regulatory structures are reshaping European investing and creating potential for long-term renewal.

28 August 2025